On February 5th last year a photo of several female members of the Democratic party was tweeted by the account “Red Nation Rising”. The women were dressed in white KKK-uniforms. Afterwards, the photo and other versions of it were circulating on Twitter, and several people, among others a famous radio host, posted the photo.

The actual story behind the photo is that democratic women carry on a tradition where they attend the State of the Union-speech dressed in white in reference to the women’s suffrage movement and wear lapel pins with symbols of the Equal Rights Amendment and climate change. However, many saw this as an opportunity to smear the democratic women as KKK-members.

The image is an example of what the American professor Betsi Grabe calls ‘fake news’. Fake news is in the Cambridge Dictionary defined as »false stories that appear to be news, spread on the internet or using other media.«

The spread of false information

On February the 24th the professor and former dean at The Media School of Indiana University Bloomington visited RUC to talk about how fake news, dis- and misinformation are spreading within social media and how it has impacted on democracy.

»The efficiency with which mis- and disinformation is spreading at this point is unprecedented, so therefore I think it is urgently necessary to act,« Betsi Grabe says.

Difference between mis- and disinformation:

Misinformation is not an intention to mislead people.

Disinformation is an intention to mislead people.

Source: Betsi Grabe

The media has become more and more a platform for mis- and disinformation which is hard to identify, where citizens are manipulated or just unknowingly will spread these incorrect messages. A study from Brown University has found that Twitter bots on an average are producing a quarter of all tweets about climate a day. Twitter bots are automated Twitter accounts that interact with Twitter, such as tweeting, featuring a certain hashtag and so on to generate information and interest. Facebook disabled 1,7 billion fake accounts from July to September 2019. And Pew Research Center studied for a six-week period in 2018 1,2 million tweets with links and found that two-thirds of all these tweeted links were shared by suspected bots.

The former South African journalist, and now a professor in Mass Media and Communication, Betsi Grabe studies how visual media images affect our understanding of life, how cases of fake news have impacted society and how media users, journalist and politicians can deal with this. Apart from being a Media School professor, she is also the co-leader of the center ‘Observatory on Social Media’.

»Information and the integrity of information is the lifeblood of democracy. If you don’t have reliable information that flows through our society, how can citizens become informed and how can they vote, when it is based on information which aims to deceive and manipulate?« she says.

Visual media are powerful

Visual media are a vital key to information and emotions. The human brain is well adjusted to visual processing to the point where we attend to images with high levels of automaticity. So, we don’t think about it.

»It takes a fraction of a second for us to recognize an image and respond to it,« she says and adds that in 2025, 85% of what we consume on our mobile devices will be audiovisual media according to the predictions.

»If you don’t have reliable information that flows through our society, how can citizens become informed and how can they vote.«

Betsi GrabeTherefore, Betsi Grabe sees the visual media as a powerful mode of communication, but also as a powerful tool to provoke emotions. She argues that the explanation for this is biological. The pathways in our brain that process images are very closely connected to the pathways that process emotions. And so, images take a shortcut when the purpose is to provoke emotions.

»Images are not as explicit as language and words, so you can get away with very powerful messages where no one will be able to put a finger on what the image is actually communicating. In an instant, an image can provoke emotions, and convey meaning, but at the same time it is very difficult to pinpoint where in that image meaning is located,« she says and underpins that this is an important factor for why media images can be seen as the steamroller of misinformation.

Memes and deepfake

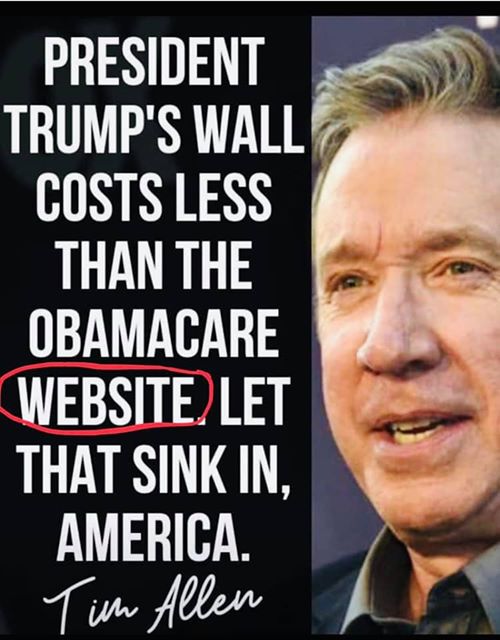

A good example of a visual media, which can be interpreted differently, is the so-called memes, which are particularly images and videos that takes a funny perspective on something.

An example of a meme that produced fake news, was when the Facebook page ‘ChairmanSizer’ on September 14th, 2019 published a photo saying that the actor and comedian Tim Allen has stated, that Trump’s Wall between USA and Mexico cost less than the Obamacare website. This statement was later tweeted by Donald Trump’s son, Eric Trump. Even though it was fake news and also a statement that was attributed to the wrong person, the meme still got an estimated view of 5,728,560.89 according to the non-profit Avaaz.

Betsi Grabe says the motivation to share memes could take many forms — the account holder may believe the images are real, foster a sense of humour or it could be ideological tribalism, Betsi Grabe emphasize.

Another example of a visual media that provoke concern, Betsi Grabe mentions, is the technological feature ‘Deepfake’, where you can feed a few thousand images of a person into a machine learning program and build an animation of that person, add sound to it and make it say things:

»There are many places, including Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), working on detecting deepfakes. But at this point that technology is not quite available to the public—while the apps to make deepfakes are,« she says.

The most known deepfake video is comedian Jordan Peeles imitation of Barack Obama, which was made to warn the public about this technology.

Focus on media literacy

Since, it is so difficult to identify disinformation, Betsi Grabe also advocates strongly for more media literacy in the school curriculum which, according to her, is almost nonexistent in America at the moment.

»More information has been produced and disseminated through media during the lifetime of high school students than during the entire history of homo sapiens that predates them. Navigation skills through this media environment are therefore of utmost importance to distinguish between credible and non-credible information,« she says.

Even though we have more information available to us, Betsi Grabe believes that the world is getting smaller because we surround ourselves with the ideas we already believe.

»We tend to find information in our environment to confirm what we believe in rather than to encounter what we do not believe in,« she says.

The only way to address this, which is a challenge for human beings, Betsi Grabe states, is to expose ourselves to news outlets that directly contradict our own ideological biases.

»We tend to find information in our environment to confirm what we believe in rather than to encounter what we do not believe in.«

»To stay connected with your fellow citizens, you need to know what they think about the world,« she says and adds that if we do not do this, we will be pulled apart in echo chambers where we surround ourselves with likeminded people, and thus we lose a sense of society as a larger entity and become polarized in the process.

Once we live in these small echo chambers, Betsi Grabe says, we are vulnerable to disinformation.

»If it is disinformation that confirms our own viewpoint, we often pass along this information, without knowing that we do,« she says.

Spot the bots

Another way to address and identify misinformation is to do a network analysis of the distribution of information. Betsi Grabe describes this analysis as visually mapping the connection between accounts as they spread information. Betsi Grabe collaborates with colleagues at The Observatory on Social Media(OsoMe) who built tools to detect bots on social media. These tools are not hard to use and available to anybody for free.

»When you suspect a Twitter account of a bot-like activity, you can use the OsoMe ‘Botometer’and based on scores of how that account behaves in the larger social network, the tool tells you the likelihood that the account is a bot or a human,« she says.

How to detect a fake twitter account:

You can look at several characters of a post and an account that will signal to you that something is wrong:

– A very long user account name

– The behaviour of the person who holds the account

– How new is the account?

– Is it an account that tweets original material or repurposing existing material? If this account is already pushing up existing material, it is a good indicator that this is misinformation and that there is a bot sitting behind it.

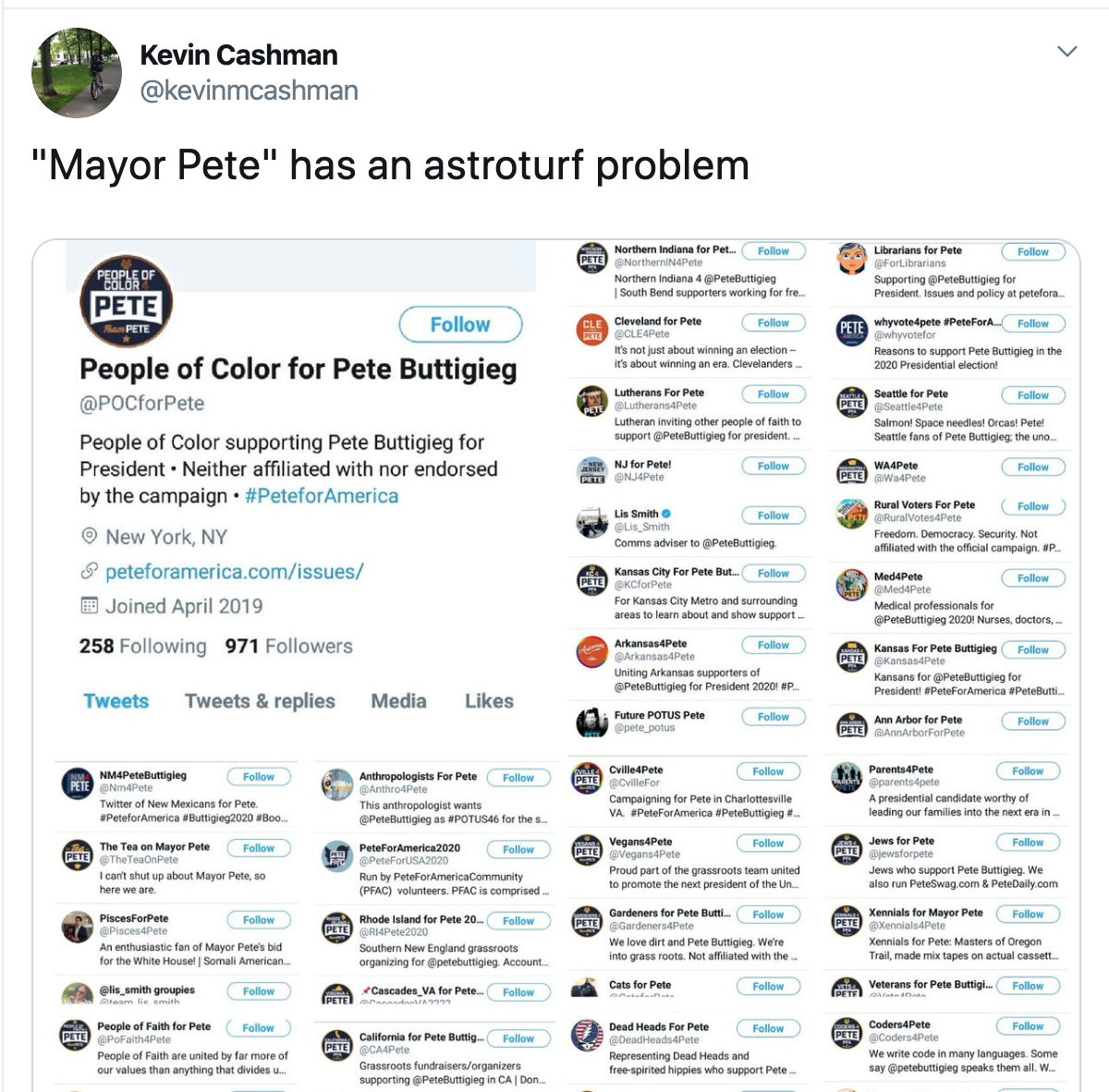

The politician’s way of using bots

There are all kinds of ways in which politicians have used bots to spread information and launch campagnes in very coordinated ways. ‘Astroturfing’, for example, is a way of creating the perception in an online environment that a person, or say a candidate, is popular to the point where a bandwagon effect of support is created for a candidate that is not there. At least not to the extent that astroturfing is making it look.

»It appears to be grassroots support, except it is not,« she says.

The senior associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research Kevin Cashman tweeted a photo of several ‘4pete’ accounts supporting the former democratic candidate Pete Buttigieg. He pointed out that maybe this was a phenomenon of astroturfing. However, it is up for debate whether it is astroturfing or not. Screenshot

Alongside, Betsi Grabe points out one new phenomenon that are going to be more present during the American election 2020, and that is local fake news websites. More than 400 of those have been identified. They are made to look like local news.

»If people believe these stories, because they confirm specific opinions, they will strengthen these echo chambers,« she says and adds that initial analyses of their content shows a right center of ideological leaning.

Trust issues in Denmark

Betsi Grabe has also taken a look at the current Danish media ecosystem. And what she finds alarming about news media use in Denmark is that, just like in America, Danish people tend to mistrust mainstream media:

»When the public does not trust news media, they become vulnerable to disinformation.«

People who hold more populist political views in Denmark tend to trust media even less, which Betsi Grabe says suggests that Danish society might be in the early stages of polarization.

But what are the consequences of unchecked mis- and disinformation? Betsi Grabe thinks it will lead to polarization that will make debate between people impossible:

»If you let mis- and disinformation run free, it would literally pollute the information environment to a degree where people would believe things that are false but aligns with their beliefs. And they will dig deeper and deeper into this view.«

Betsi Grabe argues that it is good idea for academics to partner with each other across disciplines, with journalists and the public to create the means to advance media literacy and to work on policies to stop the flow of disinformation.

Top 5 fake news stories of 2019:

The non-profit organization Avaaz has made a report, where they range top 20 fake news stories on Facebook in 2019 by the number of estimated views, the stories have. Here are listed the top 5 of them.

1. “Trump’s grandfather was a pimp and tax evader; his father a member of the KKK” where the estimated views are 29,202,552.80

2. “Nancy Pelosi diverting Social Security money for the impeachment inquiry” where the estimated views are 24,606,644.49

3. “AOC proposed a motorcycle ban” where the estimated views are 12,380,492.64

4. “Trump Is Now Trying To Get Mike Pence Impeached” where the estimated views are 10,888,995.03

5. “Ilhan Omar Holding Secret Fundraisers With Islamic Groups Tied to Terror” where the estimated views are 9,327,885.40